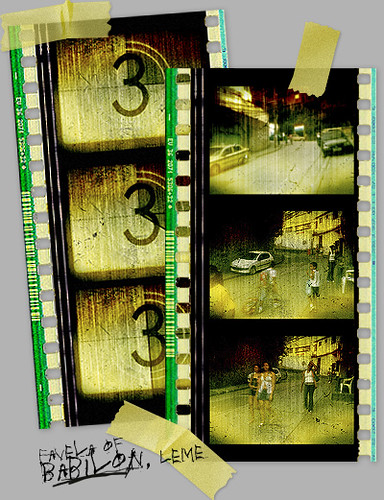

A view from my window had it's fifteen seconds of fame when the Brazilian film Tropa de Elite, directed by José Padilha, picked the Golder Bear for the best film at the 58th Berlin Film Festival and shocked the audiences with a merciless description of police violence. Film starts with police cars racing up the ladeira - a curvy, steep road climbing up the hill to the favela - just outside my window, to a baile - a funk party - that in a few minutes turns into a blood bath.

Now the road up the hill to the favela of Babilônia is quiet. On a crude brick wall, a throw-up reminds the passers-by that Leme is the property of CV. There is no need for explations, everyone knows that CV stands for Commando Vermelho. A few guys are hanging around the entrance to the favela, laughing and chatting up the passing locals. I don't know if they are guards on the watch for the police or just youngsters doing what the yougsters do on a friday night. Occasionally a series of firecrackers goes of, a warning from falcões, the scouts watching over the favela. But there are no guns visible, big or small.

Dynamics of power: The favela logic

Favelas in Rio de Janeiro are the nexus of a complex web of power and violence. Organized crime, community organizations, churches, businesses, different types of police forces and politicians, all have their part to play. And most importantly, there are of course the regular people inhabiting the favelas: over one third of Brazil's urban populations lives in slums.¹

All the favelas are controlled by one the three leading drug trafficing organizations: Commando Vermelho (CV, "Red Command"), Terceiro Commando (TC, "Third Command") and Amigos dos Amigos (ADA, "Friends of Friends"). These are powerful criminal factions with armies of soldiers armed up to the teeth, carrying modern military-grade weaponry, from machine guns to sniper rifles and hand granades. Their main business is controlling the drug traffic in the city. The factions rule the shanty-towns with a cruel but efficient hand: Theft and other kind of crime in favelas is quickly and heavily punished, death-sentences being far from uncommon. This makes the situation so complex. As most favelados - the residents of favelas - percieve that the city and the state have abandoned them - and they probably are right to a certain extent - the factions fullfill a social need. Their rule is not exactly democratic, but they do provide security, some basic services and pay for entertainment like bailes. In exchange, the residents accept their activities within the community and keep their mouths shut should the police dare to come sneaking around. The factions have created themselves an image as social bandits, modern-day Robin Hoods, as is illustrated by Paul Sneed's highly recommendable research work Machine Gun Voices.²

The factions rule the shanty-towns with a cruel but efficient hand: Theft and other kind of crime in favelas is quickly and heavily punished, death-sentences being far from uncommon. This makes the situation so complex. As most favelados - the residents of favelas - percieve that the city and the state have abandoned them - and they probably are right to a certain extent - the factions fullfill a social need. Their rule is not exactly democratic, but they do provide security, some basic services and pay for entertainment like bailes. In exchange, the residents accept their activities within the community and keep their mouths shut should the police dare to come sneaking around. The factions have created themselves an image as social bandits, modern-day Robin Hoods, as is illustrated by Paul Sneed's highly recommendable research work Machine Gun Voices.²

The favelas hardly offer opportunities for the young people to get an education or a job, despite the best efforts of numerous volunteer organizations. That makes joining the drug gangs often the most lucrative - and regularily only - career option for the kids growing up in Rio's shanties.

The other side of conflict, represented in the favelas by the occasional invasions of the police, are seen as either corrupt and hopelessly ineffective - which sadly usually is true - or as brutal murders - which also unfortunately is often true, especially in the case of the BOPE-forces, the subject of the film Tropa de Elite. The letters stand for Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais. BOPE is the black-uniformed elite division of the Military Police, specialised in urban warfare - in other words missions in the favelas - and known for both cruelty and incorruptability. Just seeing them guarding a plaza in the centro in the broad day-light - carrying piles of bleeding-edge killing technology - is enough to send shivers down my spine. In the shanties, they are usually seen riding in the caveiraos, "big skulls": fearsome armored vechicles named after the troop's skull symbol.

But of course also the police force consists of regular people. The corruption is a deeply rooted epidemic in the public services. For regular cops out on the street, the main reason for accepting bribes is probably the next-to-non-existent salary: closing eyes on the activities of the narco-trafficers is the most certain way of getting back home to the wife and the kids in a one piece - and it also pays better. Up the ladder, corruption, hypocricy and opportunism among the politicians stir up the mess even more and they are, more or less rightfully, often seen as the root of all evil.

Most of the violence in favelas occurs between the drug factions fighting each other or the police. But innocent people do die, too, on a regular basis, due to the stray bullets and berzerker sprees on the side or the other. The violence outside the favelas, against the citizens of the asphalto, for an example robberies, is more often not related to the drug gangs but simply to the terminal poverty faced by a huge percentage of the city's population. In the end, all the violence is a result of the disgusting level of inequality in the whole country. Already in 1996 Brazil's disparities of income were second only to Botswana in the whole world, and the situation has hardly gotten better.

The Troop of the Elite

The movie Tropa de Elite received mixed reactions in Brazil, which were followed by the heavy criticism in Berlin. It was seen as fasistic and in Brazil audiences had people actually cheering when a drug trafficer hit the ground on the silver-screen. What shocked the reaction boils down to the viewpoint. The already classic film City of God (2002, dir. Fernando Meirelles) showed the street violence from the angle of the favelados on the both sides of the law. Carandiru (2003, dir. Hector Babenco) made the point that even the criminals are humans. Then the excellent TV-series City of Men presented the more peaceful side of the life in favela, often in a hilarious way, and exposed a reality that rarely makes headlines in the news papers. The series was a surprising success and continued for four seasons.

Now Tropa de Elite seems to strip the favelados of their human rights by showing the reality of the slum strictly through the eyes of the police. And not just any police, but the most efficient and brutal force of urban warfare in the world: BOPE of the Polícia Militar. Not an easy but definitely a provocative viewpoint. One might wonder what is a force trained for war doing in a favela in the first place, and that's just the start of the social complexities the movie seeks to tackle. In short, the film is a hyper-realistic story about a captain of BOPE called Nascimento - a role that made the actor Walter Moura into a huge celebrity in the country.³ After Nascimento's wife gives a birth he starts facing mental problems and wants to get out of the force. The film is a story of Nascimento crafting himself a replacement, in an attempt to redeem himself.⁴ The victim is Mathias, a young, black, idealistic policeman who dreams of becoming a lawyer. Despite the pitiless style of the film, I see it as a cruel tragedy where a Mathias' dreams are swept under the wave of violence and a man yearning to become a hunter of monsters is consciously turned into a monster himself.

In short, the film is a hyper-realistic story about a captain of BOPE called Nascimento - a role that made the actor Walter Moura into a huge celebrity in the country.³ After Nascimento's wife gives a birth he starts facing mental problems and wants to get out of the force. The film is a story of Nascimento crafting himself a replacement, in an attempt to redeem himself.⁴ The victim is Mathias, a young, black, idealistic policeman who dreams of becoming a lawyer. Despite the pitiless style of the film, I see it as a cruel tragedy where a Mathias' dreams are swept under the wave of violence and a man yearning to become a hunter of monsters is consciously turned into a monster himself.

The movie draws a vivid, bloody and often shocking picture of the dark web of violence the city is tangled into. It does not pretend to offer many answers. At least easy ones. This would be naive, an understatement of the gory mess that is Rio de Janeiro.⁵ And also hypocritical, movie seems to say, showing the rich kids from Zona Sul going for a peace march on the sunday - after they've spent the saturday night playing with fire, dealing drugs from the favela to their well-off friends. After all, it is this white demand for the narcotics that fuels the fires burning down the favelas.⁶

Beneath the action-packed surface, Tropa de Elite is a complex movie. It is not a film one would fall in love with, but it is a powerful and important film, even if not an easy one to watch. It raises more questions than offers answers. It leaves an uncomfortable feeling. Considering the subject, these are good things.

The Elite of the Troop

Before the film there was a book. Elite da Tropa, published in 2005, is written by Luiz Eduardo Soares, a political scientist and an anthropologist, with two ex-members of BOPE, André Batista and Rodrigo Pimentel. It's a work of fiction, in the sense that the names and the places have been changed and the events mixed up, but it's strongly based on the actual experiences of the authors. The book is even harder piece to chew and swallow than the movie. It starts with a little tune from the song-book of BOPE - a few roughly translated verses give you the idea: "Man of black, what is your mission? It's invading favela and leaving corpse on the ground ... Do you know who I am? I am a damn dog of war. I'm trained to kill. ... If you ask where I come from and what is my mission: To bring the death and the desperation and the total destruction."

The book is even harder piece to chew and swallow than the movie. It starts with a little tune from the song-book of BOPE - a few roughly translated verses give you the idea: "Man of black, what is your mission? It's invading favela and leaving corpse on the ground ... Do you know who I am? I am a damn dog of war. I'm trained to kill. ... If you ask where I come from and what is my mission: To bring the death and the desperation and the total destruction."

First part of the book consits of a number of short stories, illustrating various dilemmas and situations from the lives of members of BOPE. Writing is not perfect nor elegant - let's just say it's functional - but the plots tend to be clever. They create an disturbing image of the grey area of moral these men operate in, where torture is just one of the necessary professional skills, where men are systematically turned into savage dogs but yet where there still exist a strick moral code and dishonesty is punishable by death.

What hits first, from the page one, is the violence. The book goes much further than the movie: when in the film the trafficer confesses after the torture by suffocation, mercifully before one of the officers pushes a broom up his rectum, in the book the officer goes all the way with the broom. That chapter is with a somewhat grim humour named Sexo é Sexo - "Sex is Sex". This is just one example of the book´s detailed descriptions of torture and murder.

Second part of the book book steps two years forward and presents reader with one longer story. And, curiously, at some stage the reader has become numb to the violence and the most disgusting parts of the book turn out to be the ones that describe the ruthless opportunism and selfishness of the politicians and the corrupted part of the police force. This theme is central to the second half of the book, during which the real enemy reveals it's face. Unfortunately, on the second half the book also loses much of it's power, becoming a clumsy conspiracy thriller.

Like the movie, the book excells at forcing the reader to form an opinion and pushes him beyond the most obvious ideas. But written word has a power to drag the reader very deep into the head of the character. So deep that, whether this is intention of the authors or not, it gets hard to see the favela from the shacks. The first half of the book suffers from the fact that the only viewpoint you have is that of the narrator. And he doesn't give much options, constantly repeating same arguments: "Accept my truth, like it or not, or keep your head stuck in the sand, I don't care." And I cannot accept his truth, methods or most of his arguments and thus the narrator inevitably pushes me away from the book too.

Lost in Babilônia

"In Barra, two citizens were murdered during following days... Why not rule a death penalty for these cases? It would be a just response to innocents' outcry for blood", writes a reader on the letters-page of O Globo, Rio's main newspaper. The pages of the local news are filled with crimes: 17 people are murdered daily in the city. I can imagine how tired the people are of the all the violence. Everyone has either experienced it or lives in the constant fear of it. I can imagine how frustrating the problem seems when there are hardly easy solutions in sight. I can imagine that people are starting to feel so tired that just killing 'em all seems like a viable solution. But it must not be.

When I for the first time climbed up that ladeira, it was because I'd been asked to come to Babilônia to film a capoeira practice. It was already dark when I got here: a quiet friday night. A few times I ducked at the last moment to dodge a motorcycle taxi. They are an example of favela inventing it's own ways to get by the everyday-problems, like the exhausting walk up the road: for two reals you're taken with a motorbike where every you want on the hill. But of course when coming down the road they spare gas by keeping their engines off, silent ghosts rolling through the darkness. Finally getting to the top I ended up hopelessly lost among the shacks, crossing paths, stairs going up and down, trees and deep shadows. I wasn't sure if I should be scared, but I considered it the most efficient policy for my safety to supress any sign of fear. I decided that the attack is the best defence and asked everyone for instructions. It took me a while to get to the capoeira hall - I even ended up chatting for half an hour with the president of the community - but everyone gave their best effort to help me.

Finally getting to the top I ended up hopelessly lost among the shacks, crossing paths, stairs going up and down, trees and deep shadows. I wasn't sure if I should be scared, but I considered it the most efficient policy for my safety to supress any sign of fear. I decided that the attack is the best defence and asked everyone for instructions. It took me a while to get to the capoeira hall - I even ended up chatting for half an hour with the president of the community - but everyone gave their best effort to help me.

A friend living in the neighbouring favela told me yesterday how the cops had again raided their community the previous night. But in here, I've seen no guns. There are, of course, guns in the favela. But they are not blazing every day.

- - -

Notes

1) 36,6 percent of the Brazil's urban population - amounting up to 51,7 million people - lived in a favela in 2003 according to estimates of United Nations presented in Mike Davis' book Planet of Slums (London, 2006). The same book shows how Rio has grown from 3,0 million inhabitants in 1950 to 11,9 million in 2004, a rate of urban growth extremely hard if not impossible to control in a sustainable, planned fashion, inevitably resuting in a exploding number of slums.

2) Paul Sneed (Machine Gun Voices: Bandits, Favelas and Utopia in Brazilian Funk, 2003) summed up the role of trafficers elegantly: "The drug traffickers of the hills and favelas of Rio de Janeiro: demonized and romanticized, pre-modern and post-modern, social bandits who are oddly millenarian even as they are anti-revolutionary, the fear, neglect and complicity of the middle- and upper-classes have allowed them to come to power and helped them to stay there. The poor have made them their champions, albeit reluctantly, and they have come to occupy a crucial role in the administration of power in the larger Brazilian social order... Now, the “divided city” is the great challenge for the restored democracy in Brazil in the years after the military dictatorship."

3) In the light of the generational change between Brazilian film-makers, shed by Carlos Diegues in essay Como as Coisas São in a recent book on Brazilian cinema, Cinco Mais Cinco, what might be mistaken for nihilism in Brazilian cinema could be rather seen as a part of the younger generation's move from idealism towards realism, from utopianism to individualism. "Para o Cinema Novo, imporatava cultura e politica; para os cineastas da Retomada, arte e tecnologia." ("For the Cinema Covo, important was culture and politics, for filmmakers of Retomada, art and technology.") A political message might be implicit in the story but is never placed before the realism and the artistic purposes. I've included here a few further notes based on that essay, since I feel that they provide a useful background for the Padila's controversial film.

4) This hope of redemption for Nascimento is not without parallels in Brazilian cinema. Diegues writes: "Como essa lute é individuel e ninguém, a princípio, deve estar solidário conosco, a única proteção em que ainda podemos confiar é a do que nos restou da harmonia natural da família... a família é uma espécie de lugar de suspensão da luta contra o outro, onde o poder se disputa e se exerce de outra maneira, em nome do amor." ("Like this fight is individual and no-one, in principle, should support us, the only protection in which we always can trust is the one remaining in the natural harmony of the family... family is a kind place of suspension from fight against each other, where power is disputed and exercised in in another manner, in name of love.")

5) According to Diegues, the cities have become symbols of hell in Brazilian cinema. "Não se trata mais de procurar uma harmonia com os outros para viver bem e em paz; trata-se simplesmente de sobreviver... Nesse esformaço solitário por sobrevivëncia e se possível ascensão, amizade, amor e sexo, são, de fato, meros exercíos de poder." (One does no more seek to find a harmony with others to live well and in pace; one simply tries to survive... In this solitary attempt for survival and if possible, social ascension, friendship, love and sex, are, in fact, mere excersices of power.") Against such a bleak view of the life in Brazilian cities, it's hardly surprising that the ethic of kill or be killed is shown as a natural process of survival. Everyone is using the means of power available to them, and on the level of streets it comes from the barrel of guns. Again, this does not imply it is right, but the way the realism of contemporary Brazilian cinema chooses makes it's point: by showing the things as they are.

6) After being awarded with the Golden Bear, Padilha explained his aims and corrected misunderstandings in Jornal do Brasil ("Filme 'Tropa de Elite' ganha Urso de Ouro em Berlim", 17.2.2008): "Fiz o filme sem partir de idéias marxistas ou neolibérais. O princípio foi o de levantar as regras de vida de cada grupo de personagem e como eles fazem suas opções a partir delas." ("I did the film without marxist or neoliberalist ideas. The principle was to show the rules of the live of each group of characters and how they create their options onwards from those.")

Sunday, March 2, 2008

Big Skulls and Men in Black

Lähettänyt

TeemuK

klo

10:13 PM

![]()

Tunnisteet: Brazil, movies, politics, Rio de Janeiro

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Damn, you've been doing your homework out there, no lack of references here. Thanks for the read.

Post a Comment